What’s left of the ‘Mandal moment’, politically and socially, now? : Christophe Jaffrelot

Rise of Hindutva politics and contradictions within OBC spectrum have exhausted the silent political revolution. Unfulfilled promise of job quotas may lead to a revival.

Thirty years ago, the then prime minister, V P Singh implemented the Mandal Commission report, initiating what I have called a “silent revolution”. It triggered a socio-political process that resulted in some social emancipation and the rise to political power of plebeians at the expense of the upper and dominant castes.

The Mandal moment was primarily political, even if what was at stake was the extension of positive discrimination through a 27 per cent quota for the OBCs in the civil service. The upper castes instantly mobilised to prevent a reform that would curb their public sector job opportunities, which was valuable prior to the economic liberalisation of 1991. Their resistance aroused indignation among the lower castes and resulted in a consolidation of OBC groups. Many OBCs stopped voting for upper-caste notables and preferred to elect representatives from their own social milieu to Parliament.

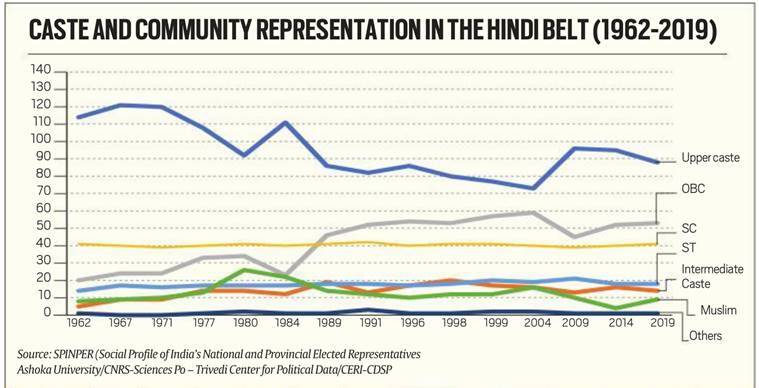

In the Hindi belt, the percentage of OBC MPs nearly doubled from 11 per cent in 1984 to more than 20 per cent in the 1990s, whereas the proportion of upper-caste MPs dropped from 47 per cent in 1984 to below 40 in the 1990s. By 2004, upper-caste presence in the Lok Sabha had fallen to 33 per cent, while 25 per cent of MPs were OBCs. This turnaround was thanks initially to the Janata Dal, and later, to its regional offshoots, including the Samajwadi Party in UP and the Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar.

Though the Janata Dal disintegrated in the early 1990s, it did not affect the dynamics of democratisation the party had set in motion. First, all parties, including the Congress, were forced to field several OBC candidates having realised that they could not rely on old clientelist mechanisms to get upper-caste notables elected. The OBCs constituted over half of the population and the new “OBC vote” could not be ignored. Second, new public policies designed for the OBCs were implemented not only by the parties representing them, but also by the Congress. When it returned to power in 2004, the Congress set a quota of 27 per cent for OBCs in public universities. This decision, known as Mandal II, once again provoked the ire of the upper castes. So what’s left of the “Mandal moment”, politically and socially, now?

This “silent revolution” brought on a counter-revolution, a revenge of the elite whose vanguard has been the BJP. The BJP’s Hindu nationalism had the advantage of transcending caste identities in the name of Hindu unity and its fight against the threat from Islam. This backlash culminated in 2014, when the Hindutva version of national-populism gained traction with some OBCs because of the alchemy achieved by Narendra Modi — for the first time, the leader of the BJP was a pure product of the RSS who belonged to an OBC caste. As Modi presented himself as a self-made man, a former chaiwallah, and did not defend positive discrimination, he was the perfect antidote to Mandal for the middle-class upper castes. By taking the BJP to its first electoral triumph, Modi also allowed upper castes to consolidate their position in the Lok Sabha at the expense of the OBCs. In 2014, the percentage of MPs from the upper castes rose to 44.5 per cent, on a par with its representation in the 1980s, whereas the share of OBC MPs dropped to 20 per cent, according to the database SPINPER (Social Profile of India’s National and Provincial Elected Representatives) built by Ashoka University and CNRS-Sciences Po.

Modi did not attract OBC voters only based on his plebeian background and Hindutva. He also submerged caste politics in the name of development and class. He presented himself as the defender of the “neo middle-class” that had come into being in the 2000s owing to the rise of OBCs who had benefited from the Mandal quotas and economic growth. Young OBCs were migrating from the village due to the attraction of jobs. Even if such jobs were unstable and badly paid, they usually enabled these former rural inhabitants to improve their living conditions. Modi’s neo middle-class discourse was class-based but had no affinity with socialism. On the contrary, instead of asking for more equality and redistribution, it made merit the number one criterion of social justice, a repertoire that had become gradually hegemonic after the1991 reform but which the UPA government balanced with some socio-democratic policies (including Mandal II).

If Modi sealed the fate of quota politics, the “Mandal moment” was over many years earlier. OBC politics has been a victim of the success of OBC policies in two ways. A saturation point was reached when the Centre and states introduced the 27 per cent OBC quota and the judiciary refused to allow the total amount of reservation to go beyond 49 per cent. Parties representing the OBCs could no more say, “vote for me, you’ll get more reservations”.

Second, some jatis within the OBC spectrum benefitted more from the reservations than others. The Yadavs are a case in point. We can infer from the Indian Human Development Survey that they have cornered more reservations than others. In UP, 14.5 per cent of the Yadavs occupied a salaried job in 2011-12 (the last round of the survey) against 5.8 per cent for the Kurmis, 5.7 per cent for the Telis, 6.7 per cent for the Kushwahas, 3.5 per cent for the Lodhs.

The Yadavisation of UP and Bihar, during the rule of the SP and RJD respectively, has divided the OBCs. Some jatis were alienated, to such an extent that they started not to vote along with the Yadavs. In Bihar, Kurmis followed Nitish Kumar and created a separate party as early as 1994. In UP, the BJP was shrewd enough to nominate candidates from non-Yadav jatis in order to consolidate a non-Yadav OBC vote by capitalising on the resentment of these castes vis-à-vis the Yadavs. This strategy was obvious in the 2019 elections when poor OBCs voted more for the BJP than for the BSP-SP alliance despite the elitist image of the former — 59 per cent of the “poor” OBCs supported the BJP, against 33.5 per cent who turned to the BSP-SP alliance.

The reason why the “rich” and “middle” class OBCs voted more for the BSP-SP alliance than the “poor” OBCs becomes clear the moment the jatis are factored in: The SP remains a Yadav party to a large extent and Yadavs tend to be richer than Gadariyas, Kushwahas, Telis and Lodhis, who resent Yadav domination and the way the latter has cornered a large proportion of the reservations. The unity problem affecting the OBCs is similar to the one confronting the Dalits in UP — the non-Jatav SCs resent the socio-economic rise of the Jatavs and distance themselves from the BSP, which is seen as a Jatav party. Many of the non-Jatav SCs vote for the BJP now. This push factor, however, is reinforced, in the case of the lower OBCs as well as the lower SCs, by a pull factor. By supporting the Hindutva forces, these jatis also try to sanskritise themselves and be accepted by the Hindu “high tradition”.

So, is it “game over” for Mandal politics? Not necessarily, given the fact that if quotas have been granted to OBCs they are not fulfilled. In 2015, OBCs represented only 12 per cent of Class A employees in the central government services, 12.5 per cent of Class B and 19 per cent of Class C workers — which meant 18 per cent of the total workforce, almost 10 percentage points less than what they had been promised in 1990. It is a deficit OBCs may consider worth fighting for.

This article first appeared in the print edition on August 22 under the title “Mandal moment, 30 years on.” The writer is senior research fellow at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS, Paris, professor of Indian Politics and Sociology at King’s India Institute, London, and non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.